Update, February 28, 2022: Unconfirmed reports have emerged from Ukraine suggesting the largest airplane in the world, Antonov’s An-225 Mriya, has been destroyed during the Russian takeover of Hostomel Airport, where the plane had been undergoing maintenance.

Ukraine’s Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba tweeted on February 27 that the six-engine aircraft, initially built to ferry the Soviet Union’s Buran space shuttle, had been destroyed. Ukrainian state defense company Ukroboronprom, which manages Antonov, released a series of statements—the first of which claimed the plane had been destroyed and the second of which claimed it was too early to tell the full extent of the damage.

Antonov tweeted Sunday evening that they could not confirm the plane’s “technical condition” because it has not yet been inspected by experts.

Every year, hundreds of people travel the world just to glimpse one particular airplane. This isn’t some experimental aircraft or even a fancy fifth-generation stealth fighter. This is a cargo plane—the largest one in the world and the only one of its kind in existence.

This is the Antonov An-225 Mriya.

And all these thronging crowds of planespotters are understandable. Mriya is a freight plane with cargo best described as ‘atypical,’ including giant turbines, entire rail locomotives, or ready-to-eat meals…for an entire army. The An-225 also makes only a couple of flights per year and just finished an 18-month-long stint off the runway.

But why would you need a plane that’s so monstrous? The short answer: Rockets.

We’re Going To Need a Bigger Plane

In the early 1980s, the Soviet Union had a problem—its rockets were too big.

In response to the American space shuttle program, Moscow placed its space dreams on the shoulders of the new Buran space shuttle and Energia super rocket. But the massive size of this new space hardware couldn’t fit on existing infrastructure for transport to the Baikonur Cosmodrome in modern day Kazakhstan, thousands of miles away from the nearest seaport.

Soviet leaders considered every conceivable mode of transportation, including oversized highways and even a scaled-up railroad. But realistic options were quickly narrowed down to air transport, but no existing Soviet aircraft had nearly enough capacity to carry such a large payload. The brand-new Mi-26 helicopter could lift up to 26 tons, but during one trial flight, a slight turbulence caused ominous pendulum swings of the simulated cargo.

Instead, Soviet engineers first considered giving the job of transporting Buran to the An-124 Ruslan, which first flew in 1982. But initial studies at the Antonov Design Bureau in Kyiv quickly showed that even a partially assembled Buran and components of its rocket carried on its back would mess up the airflow around the plane’s giant vertical stabilizer. So to fix the problem, a seven-meter extension into the already huge fuselage of the Ruslan was proposed—but even that wouldn’t be enough.

With plans to retrofit the An-124 reaching a dead end, Moscow began considering an even bigger plane. This monstrous aircraft would be like the An-124, but on steroids. The project became known by the codename ‘Article-400,’ a nod to Ruslan’s original codename ‘Article-200.’

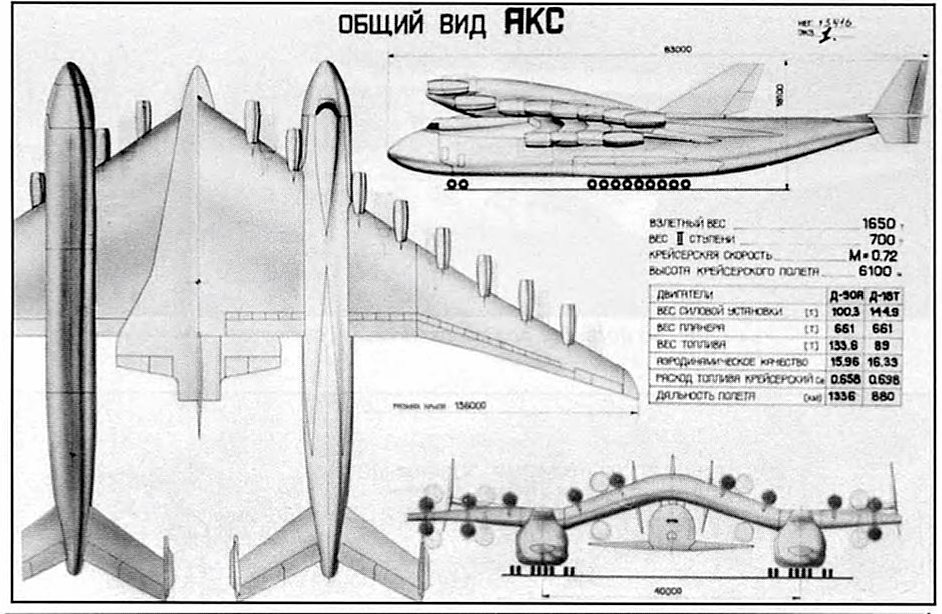

Article 400 would later be known as the An-225. As its name suggests, the An-225 would carry up to 225 tons of internal cargo (a fully-loaded Buran orbiter weighed just over 100 tons and would ride on its back). Engineers at the Antonov Design Bureau even considered a larger aircraft, called Gerakl (Heracles), which could serve as a flying launch pad for a large space plane. But the plane never materialized.

In the end, the An-225 was the Soviet’s best bet, but its development lagged well behind the Buran and Energia, so engineers went looking for an interim solution, retrofitting an old bomber into a shuttle-toting transport aircraft called the VM-T Atlant.

Building the Beast

In 1985, Antonov got an official order from the Soviet Ministry of Defense to develop the An-225. Petr Balabuev, informally known as PV, was put in charge of the project and Anatoly Vovnyanko was a hands-on manager of the plane’s development.

Balabuev gave Vovnyanko strict orders to stay as close as possible to the Ruslan—but it wasn’t easy. In the most radical move, the center section of the Ruslan’s wing was redesigned to accommodate three engines, instead of two. The new plane also lost its aft cargo entrance to give it more structural strength. The number of landing gear assemblies on the sides of the fuselage was increased from 10 to 14, and the three last rows of wheels were steerable so the giant plane could make a turn on a runway.

To maintain balance, the front section of the Ruslan’s original fuselage was stretched by eight meters, but the aft section was shortened by one meter to compensate for the plane’s heavy dual stabilizer. Vovnyanko believed the An-225 needed the dual tail for better stability while carrying cargo and to provide enough clearance for launching the top-secret 9A-10485 mini-shuttle, later known as MAKS. Even from the outset, the developers envisioned the aircraft as not only a transport plane, but also a flying launch pad for future space vehicles.

The An-225 program was given just two years to complete, but it took twice as long. The resulting aircraft—reaching 640 tons when loaded—was so big that Antonov did not have an appropriate hangar for it, so the plane had to be placed diagonally inside its final assembly hall. All its major components had to be delivered directly to the site at the right time because there was no warehouse space to store them.

For the official rollout on November 30, 1988, the specialists had to oil the floors to rotate the aircraft along the centerline of the assembly hall. Because of its gargantuan size, the plane stuck out of the hangar at the start of the ceremony.

At the time of its public debut, An-225 was christened “Mriya,” which means “dream” in Ukrainian. It was the first time that a Soviet aircraft received a Ukrainian name, reflecting the ongoing liberalization of Soviet society under leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Gorbachev and his wife Raisa came to see the magnificent machine in person.

On December 21, 1988, test pilot Aleksandr Galunenko lifted Mriya off Gostomel airfield near Kyiv for the first time. According to Galunenko, the aircraft set as many as 110 world records during its early test flights.

A Plane In Search of a Mission

An-225’s original mission was to carry the Buran shuttle and its Energia super rocket on its back from their production factories in Russia and Ukraine to the Baikonur spaceport in Kazakhstan. The Mriya would also transport the Buran shuttle if it landed at one of the USSR’s backup runways. Because of its massive size, the An-225 would be the only way to get the orbiter back to Baikonur in one piece.

But the plane arrived too late. The Buran orbiter made its first—and last—flight barely a month before Mriya took to the skies and the increasingly cash-strapped Soviet military lost interest in the expensive Energia-Buran project.

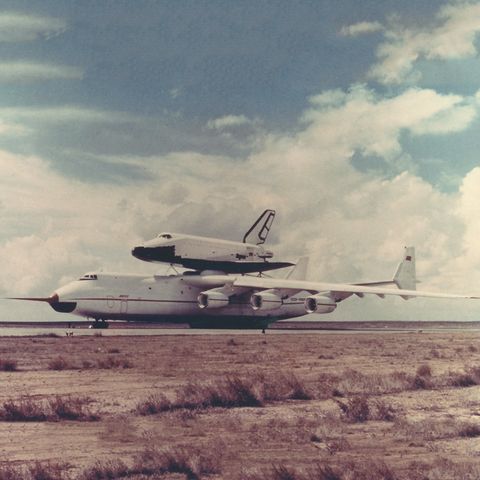

Regardless, the world’s largest plane arrived at Baikonur Cosmodrome on May 13, 1989, and made a test ride with the Buran orbiter on its back. It then carried the Soviet shuttle to the Paris Air Show in Le Bourget, where amazed spectators couldn’t begin to imagine that this impressive appearance was actually the swan song for the Buran shuttle and the start of Mriya’s long retirement.

As the USSR collapsed in 1991 and the post-Soviet aerospace industry struggled for survival, various exotic (and wacky) uses for An-225 were proposed. One idea involved converting Mriya into a triple-decker passenger jet, complete with private bedrooms, shopping malls, and a casino.

Other space projects in Russia, Ukraine, and the U.K. eyed Mriya and its planned follow-up—the An-325—as a flying launch pad for a new generation of space planes. One idea envisioned a monstrous dual-fuselage, 18-engine variant of An-225, but the concept never left the drawing board.

Three years after its first flight, the An-225 made its inaugural visit to the U.S. on a mission to pick up humanitarian aid for Chernobyl disaster victims. Unfortunately, the flight was plagued by potentially fatal technical problems and was quickly grounded. It was soon partially cannibalized for parts.

But that wasn’t the end of the Soviet’s “dream.” The Antonov Design Bureau revived the An-225 at the turn of the century, refashioning it into a commercial carrier of oversized cargo. The company also advertised plans to complete the second An-225, whose skeleton has been gathering dust for three decades in an assembly shop near Kyiv (but there is little hope that the An-225 will ever have a sibling). Despite a troubled history, the original Mriya still shows an amazing agility that’s almost unprecedented in the history of aviation—even if it’s no longer the world’s largest plane.

Today, the An-225 is still proving useful in the ongoing fight against COVID-19. On April 13, 2020, the old Soviet aircraft delivered 100 tons of medical supplies to Warsaw, Poland, becoming the largest air cargo transport by volume in history, according to the American Journal of Transportation.

Even 31 years later, the An-225 is still breaking records.